It’s the Politics, Stupid: Lessons for Germany from US Security Strategies

Photo: Thomas Kelley /Unsplash

A successful national security strategy needs a solid political foundation. In democracies, that foundation – for better or worse – rests on the electoral process and the political leaders it produces.

Key Points

- Writing a national security document is not the same as creating a security strategy.

- To be successful, a national security strategy needs a solid political foundation.

- The best national security strategies reflect the viewpoints of the current political leadership.

“We have made clear that countries that are immensely wealthy should reimburse the United States for the cost of defending them,” former US President Donald Trump declared at a 2017 news conference held to present his administration’s new national security strategy. Trump’s threat echoed some of his previous rhetoric on the failings of US allies. It also contradicted the contents of the strategy itself. The newly adopted document promised that the US would “recognize the invaluable advantages that our strong relationships with allies and partners deliver.”

This was not the only gap between the strategy and Trump’s speech. The former framed Russia as a revisionist power threatening the integrity of Western democracy. Trump’s only mention of Russia, however, was a brag about a congratulatory phone call he received from Russian President Vladimir Putin over a foiled terrorist plot. The message was clear: the US President had probably never read his administration’s national security strategy and did not seem to agree with much of its contents. The strategy could be safely ignored by enemies, allies and analysts alike. And so it was.

To Write Is Not to Create

For anyone who wants to understand what to do – or what to avoid – when writing a national security strategy, this episode contains an important lesson: a useful strategy must reflect the views of the current political leadership, no matter how distasteful the drafters may find them.

This lesson implies – somewhat counterintuitively – that the process of creating a national security strategy document is not and cannot be a process for creating strategy. Drafters often embark upon extensive workshops and outreach efforts when conceptualizing the document, but national security strategies do not emerge from dialogue and reflection processes. Such efforts may benefit analysts’ egos and the bottom lines of catering companies, but they do little to create strategy. Of course, outreach efforts are far from useless – they can help clarify, explain and promote an existing strategy to policymakers, researchers and the public. But they cannot create one.

The reason for this stark reality is simple: practical strategies stem from the domestic and geopolitical problems of a country’s political leadership, not the technocratic analyses of bureaucracies or think tanks. Too often, as in the Trump example, those writing a national security strategy see it as an opportunity to make policy through the back door. They want to use the security strategy to convince their leadership of a certain framing or agenda: that the world has changed, that leaders have misunderstood the geopolitical shifts, that domestic concerns should not outweigh foreign policy imperatives. Or – as in the case of Trump – they want to rescue the idea that allies really are invaluable.

But such efforts are rarely successful: political leaders usually have already made up their minds and are keenly aware of their political constraints. Political leaders will generally not allow their own bureaucracies to change their positions. Worse, such efforts can deepen existing divides within a polity without offering a mechanism for resolving them. Dialogue processes are not the right tools for the messy trade-offs and compromises that are the dirty business of strategy-making. The result – as we have seen time and again in the EU’s strategic dialogue efforts – often is bitter arguments over foreign policy between member states and little progress toward better strategy.

» The process of creating a national security strategy document is not and cannot be a process for creating strategy. «

The Proper Place of Politics

At its core, a successful national security strategy needs a solid political foundation. In democracies, that foundation – for better or worse – rests on the electoral process and the political leaders it produces. A national security strategy document, then, should reflect the results of a political process of strategy formulation ‒ not become an excuse to create a technocratic process.

Efforts to create a technocratic process that ‘leaves politics aside’ – as if politics were a petty encumbrance to clear thinking – miss the point entirely. In theory, technocratic processes may make more coherent strategy, but in practice, their lack of a political foundation means that they make no strategy at all. Instead, they create a document that political leaders and thus all other audiences will simply file away and forget, in the manner of Donald Trump’s strategy. If the German process for writing a national security strategy proceeds along these lines, we can look forward to a very sensible document that we can all safely ignore.

Such an outcome would be a shame, as national security strategy documents can serve an important function. Former US President George W. Bush’s 2002 National Security Strategy shows what is possible. This security strategy introduced the concept of preemption against non-imminent threats, which was later used to justify the 2003 Iraq War. At the time, researchers and analysts criticized the document for its novel and de-stabilizing interpretation of international law. But regardless of how one feels about the wisdom of that policy (and, to be clear, it was a very bad idea), the US’ 2002 security strategy was a success on its own terms. It provided a clear, coherent statement on the Bush administration’s principles and played an important role in preparing the bureaucracy, the public and many US allies for the Iraq War.

Successful Strategies Reflect the Current Leadership

The best US national security strategies have reflected the given government’s self-image – or, more charitably, its aspirations – more than the reality of its foreign policy. These documents did not attempt to describe the underlying strategy with all of its messy trade-offs: indeed, they often papered over the inconsistencies and pitfalls of their proposed policy. Instead, these strategies were attempts to convince the public of the wisdom of a chosen course, align the often unwieldy US bureaucracy with the leadership’s intent, and send a geopolitical signal to both allies and enemies. These are all worthy and important tasks, but they have little to do with making strategy.

At the moment, the German government appears divided on what kind of national security strategy it wants to adopt to deal with an increasingly geo-competitive world. Unfortunately, in this constellation, a technocratic drafting process will doom the strategy to, at best, irrelevance and, at worst, failure. Only politics, with all its unseemly compromises, can solve a political problem.

Jeremy Shapiro

Research Director, European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR)

Weiterlesen

Editors’ Note: A Strategy for the “World After”

In opinion pieces, interviews and debates, 49security will feature suggestions on how Germany can better position itself in a world that is rapidly changing. A few words on what is to come from your editorial team.

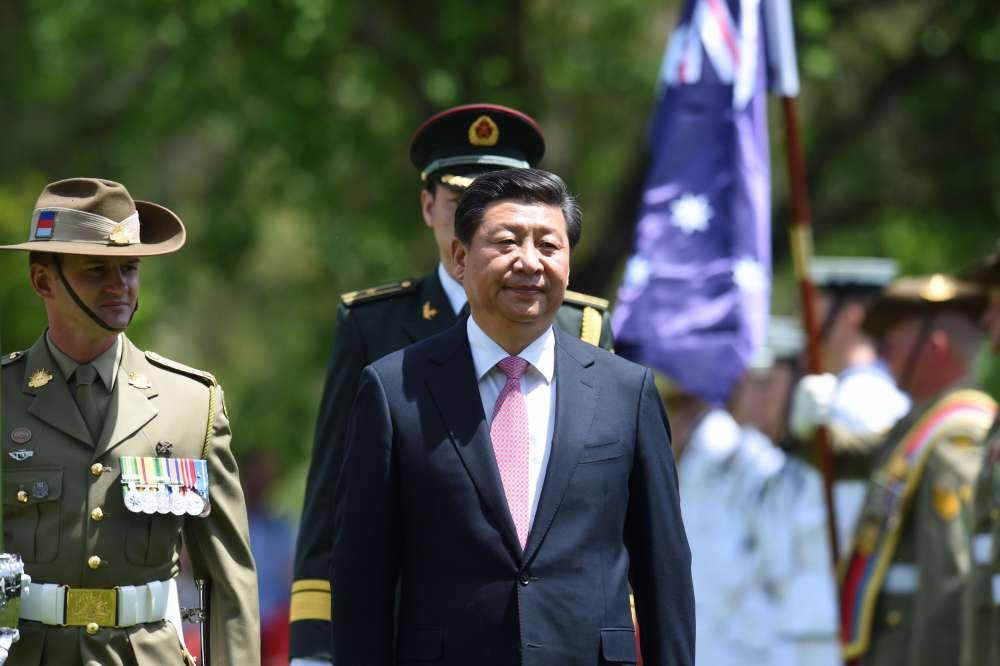

Security through Preparedness: Lessons from Australia and the Indo-Pacific

For any country with strong stakes in a rules-based order, China’s recent aggressions in the Indo-Pacific should set off alarm bells. It’s time for new thinking about national preparedness – as Australia has learned in recent years.

Wanted: Klare Leitlinien für die zukünftige Sicherheitsordnung in Europa

Der russische Angriff auf die Ukraine hat gezeigt, dass es eine kooperative Sicherheitspolitik gegenüber Moskau nicht mehr geben kann. Die Sicherheitsstrategie muss neue Realitäten reflektieren – und die deutsche Gesellschaft auf die Kosten einstimmen.