The Cost of Competitiveness: Why Germany’s Security Requires an Economic Transformation

(Jenson /Shutterstock)

Even if Germany did become more assertive in military terms, that would not solve a key problem with German foreign policy: the country’s economic dependence on exports.

At the core of German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s “Zeitenwende” speech was the idea that, as he put it, “the world is no longer the same as it was before.” This view of the significance of Russia’s renewed invasion of Ukraine was somewhat Eurocentric – even if Europe changed on February 24, it is far from clear that the rest of the world did. But Scholz overstated even the situation in Europe. If Vladimir Putin was indeed seeking to, in the words of the German chancellor, “turn back the clock to the nineteenth century and the era of great power politics,” he had already been doing so for almost a decade, since Russia annexed Crimea and invaded eastern Ukraine in 2014. Thus Scholz’s framing exonerated Germany: rather than admitting that his or previous governments had made mistakes, he implied that the situation had simply changed.

The public debate that has ensued in Germany following the speech focuses above all on security policy and in particular on the need to increase German defense spending and improve the country’s military capabilities. Beyond this, there is widespread acceptance of the notion that economic interdependence with Russia is not as squarely in Germany’s national interest or the wider European interest as it was long believed to be, even if some still argue that dialogue with Russia must continue in preparation for a new relationship with Moscow after the war in Ukraine comes to an end. Any illusions that economic interdependence might democratize Russia or turn it into a ‘responsible stakeholder’ in the international system are certainly gone. However, even if Germany has now abandoned the idea of Wandel durch Handel (change through trade) in its Russia policy, it is not yet clear whether the same goes for Berlin’s approach to the rest of the world.

Key Points:

- A strategy of diversifying German export markets is not enough. To seriously reduce its economic dependence on China, Germany needs a bigger structural transformation of its economy away from a dependence on exports in general.

- The digital and green transitions offer an opportunity to shift to a different kind of growth model – one in which domestic demand makes up a greater share of Germany’s GDP.

- A structural transformation that increases domestic demand in Germany would also be good for the rest of Europe and for the global economy.

The Real Challenge: Dependence on China

Some have argued that the war in Ukraine should prompt a rethink of German China policy – not least because China and Russia may be forging closer ties. But others, like Chancellor Angela Merkel’s former economic adviser Lars-Henrik Röller, insist that “China is not Russia” and argue that it would be premature to seek to reduce the German economy’s dependence on China.

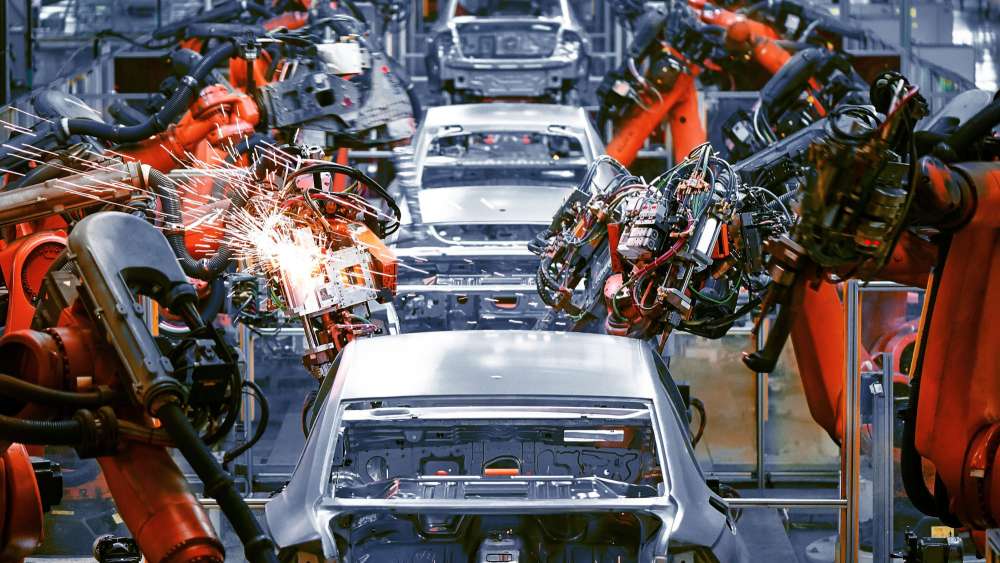

The problem is that Germany is even more dependent on China than it was on Russia. There is a tendency to overstate the overall importance of China as an export market and a manufacturing location for German companies; but what is clear is that many large and politically influential companies in key sectors of the German economy, especially in automobiles and machinery, have become extremely exposed to China, which they see as critical to maintaining their global competitiveness. Dialing back this dependence would be an even bigger challenge for Germany than the shift away from Russian gas that the German government is currently trying to accomplish. In fact, given the sheer scale of the Chinese market, it is difficult to see how Germany could ever replace it.

» Any serious attempt to reduce the country’s economic dependence on China would require a bigger structural transformation of the German economy away from its dependence on exports in general – something almost nobody in Germany is discussing. «

In other words, a strategy of simply diversifying German export markets away from China, as some in Germany have called for, is not enough. Any serious attempt to reduce the country’s economic dependence on China would require a bigger structural transformation of the German economy away from its dependence on exports in general – something that almost nobody in Germany is discussing.

Needed: A New Growth Model

Germany has always had an economy that depends on exports. However, during the 2000s, the contribution of exports to Germany’s GDP went from around a third to just under half – and has remained at approximately that level since then. Even the Social Democrats and the Greens – notionally left-wing parties – share former Chancellor Angela Merkel’s insistence on maintaining German competitiveness, which they in turn see as depending largely on maintaining Germany’s success as an Exportnation. While this strategy has produced profits for German companies and some benefits for German workers, it has also made Germany extremely vulnerable to external shocks, as the war in Ukraine has illustrated. In other words, it is a national security issue, too.

Many in Germany seem unable to imagine that a different kind of growth model – for example, one in which domestic demand made up a greater share of the country’s GDP – might even be possible. But as many economists have argued, by ending wage suppression and increasing household consumption and domestic investment – in particular, in the digital and green transitions – Germany could transform its economy in a way that would actually benefit ordinary Germans as opposed to corporations.

» By ending wage suppression and increasing household consumption and domestic investment, Germany could transform its economy in a way that would actually benefit ordinary Germans as opposed to corporations. «

A structural transformation that increased domestic demand in Germany would also be good for the rest of Europe and for the global economy. In fact, it is exactly what some of Germany’s allies and partners, including the United States even before Trump, have been asking for. Few security analysts are interested in issues that arise from economic imbalances, in particular within the Eurozone. But a serious rethink of foreign policy must include economic as well as security policy – especially in the case of Germany.

In my book The Paradox of German Power, which was published in 2014 just after the Russian annexation of Crimea, I argued that German foreign policy was characterized by a unique mixture of economic assertiveness (particularly within the Eurozone) and military abstinence (in collective defense and in military interventions outside of Europe). The Zeitenwende debate has revolved almost exclusively around Germany’s military abstinence. In particular, security analysts worry that the announced increase in defense spending and military capabilities is not materializing and argue that Germany must go even further in overcoming its reluctant to deploy military force. But even if Germany did become more assertive in military terms, that would not solve the problem with German foreign policy. In fact, without a parallel transformation of the German economy, it could make it worse.

Hans Kundnani

Senior Research Fellow & Head of Europe Programme, Chatham House

Weiterlesen

Finding a New Compass for Germany’s Foreign Economic Policy

Germany has one of the world’s most internationalized economies. This comes with benefits, but also with risks. Berlin’s national security strategy is an opportunity to recalibrate its foreign economic policy to better maneuver today’s challenges.

Bringing the Indo-Pacific into Germany’s Security Strategy

Germany’s first-ever national security strategy represents an opportunity to re-examine how Germany sees the world – not just the developments in Europe, but also those in the Indo-Pacific.

No More Navel-Gazing: A Global Outlook on National Security

For Germany’s national security strategy to work, it cannot afford to separate its national and international interests. This mindset change will require Germany to rethink how it sees itself, its position in the global order and its outlook on the world itself.