Climate Politics and the New Cold War

In the looming ‘new Cold War’, climate and security concerns cannot be separated. As Germany reconfigures its security policy, how can it minimize the effects of great-power competition on a deteriorating climate?

“Insulate homes, isolate Putin” proclaimed the European Greens in 2022. The slogan exemplifies the unexpected alignment of Germany’s national security and climate interests following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Yes, security concerns meant that European states temporarily increased their coal and liquefied natural gas (LNG) usage, but even Germany rapidly phased out Russian oil and gas after February 2022. Overall, the war has accelerated Europe’s energy transition.

One might expect the field of climate security to address this phenomenon. A mainstay of German foreign policy, climate security actors rightly argue (including on this blog) that global warming exacerbates conflicts and insecurities that threaten international stability. And yet, we also need to pay attention to the opposite side of the coin: our collective capacity to address climate change is heavily influenced by shifts in the geopolitical landscape. If we consider fighting the climate crisis as a central goal, security policymakers need to take stock of the complex climate-security links they are facing.

In doing so, there are a few core examples to consider: The war against Ukraine has ruled out Russia as a prospective exporter of hydrogen to the EU. Last year, key players in the Global South committed to non-alignment and used their new leverage to achieve the loss-and-damage agreement at COP27. China has not wavered in its support of Russia and finds itself increasingly in confrontation with the US. What this shows: a ‘new Cold War’ is looming – and it could pose the greatest challenge to the global climate effort.

» A ‘new Cold War’ is looming – and it could pose the greatest challenge to the global climate effort. «

Great Power Competition and New Climate Politics

In the United States, renewed emphasis on energy security and a surge in LNG exports to Europe surprisingly broke the deadlock on climate legislation in Congress – a process that was personified by West Virginia’s Senator Manchin (who had previously argued that Washington needed to prioritize traditional military threats). Rebranded as the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), it represents – despite considerable limitations – the most significant climate legislation in US history.

Russia’s war may have pushed the IRA over the finish line, but a closer look reveals its broader significance. The bill deliberately connects climate change to the US’ two central challenges: secular stagnation, including de-industrialization and the rise of populism, and the rise of China. In a highly polarized political environment, the need to contain China has received large bipartisan consensus. US President Joe Biden may not wield the outrageously aggressive rhetoric of his predecessor, but the IRA’s domestic content requirements (in conjunction with the CHIPS Act’s export ban on high-end semiconductors to China) are strategically calculated escalations.

For the Democrats thinking beyond 2024, the IRA represents climate realism: US decarbonization can only be sustained via a green industrial policy that strategically builds constituencies in red states – an area that some call the ‘battery-belt’ – and by reducing dependencies on Chinese solar panels, batteries and critical minerals.

From a climate perspective, this primacy of domestic politics and security interests is problematic. Although the situation is structurally different from the 1940s, the growing tensions between Washington and Beijing are creating a new Cold War that worsens the potential for climate cooperation. This stands in stark contrast to the situation in 2014 when rapprochement between the two countries – which account for 40% of annual carbon emissions – paved the way for the Paris Agreement.

Early in the Biden administration, there was hope that the US and China could compartmentalize some of their issues – compete on security and technology, cooperate on climate. On this front, last year’s G20 summit offered brief optimism in what has otherwise been a constant downward trend. It reveals the central downside of a climate policy legitimized through security logic: separating the two becomes difficult, if not impossible.

» The central downside of a climate policy legitimized through security logic: separating the two becomes difficult, if not impossible. «

In the long run, intense competition and a grand strategy of containment may result in an arms race where the two great powers attempt to outspend one another. The US currently spends 3.5% of its GDP on defense – and only 0.2% on renewable energy. While the general maxim holds that every dollar spent on defense is a dollar not spent on decarbonization, different approaches to systemic competition can have widely varying climate consequences.

In Washington, the myth of the Reagan victory school – according to which the US won the Cold War because it forced the Soviet Union to match its military spending – provides a toxic legacy. It privileges cost-imposition strategies such as the AUKUS initiative that equips Australia with attack submarines. Unlike more defense-orientated investments, this program touches the most sensitive areas of Chinese military policy (nuclear second-strike capabilities) and maximizes the likelihood of negative second-order effects on decarbonization.

Importantly, neither China nor the US are uniform entities. They each contain coalitions that seek to advance fossil fuel or green energy interests. Energy security imperatives have recently strengthened the focus on renewables in both states, but serious climate action requires significant percentages of their fossil fuel reserves to remain in the ground. Zero-sum competition will make it that much harder to leave them there.

Key Points:

- With Europe’s accelerated energy transition, it is crucial to understand that the collective capacity to fight climate change is heavily influenced by international security and geopolitical shifts.

- The US and China’s energy competition is creating a new Cold War that worsens the potential for climate cooperation and decarbonization.

- Amidst the trade-offs and opportunities of climate and security politics, Germany should acknowledge that its strategic position has implications for domestic decarbonization, work toward greater security autonomy, and put in place a greener Bundeswehr.

Zeitenwende vs. Energiewende?

As Germany reconfigures its security policy, how can it minimize the negative effects of great-power competition on a deteriorating climate? First, Berlin needs to acknowledge that how Germany strategically positions itself has implications for domestic decarbonization. Going forward, pressure from the US to economically decouple from China will only increase. This makes sense from a security standpoint, especially after Germany tragically downplayed the risks of weaponized interdependence vis-à-vis Russia until Moscow’s Ukraine invasion.

Climate concerns introduce different imperatives. One field in Germany in which calls for US-style re-industrialization have fallen on particularly fertile ground is solar manufacturing. This shift fits within long-standing narratives of a ‘solar industry lost to China’ and seems to justify immediate re-onshoring. However, as Jonas Nahm has extensively documented, the solar story is less one of naïve outsourcing than of active collaboration. For years, German Mittelstand-firms (i.e., small and medium-sized companies) in the solar sector have provided custom equipment to Chinese enterprises, which enabled the mass-manufacturing of solar panels and the previous decade’s most promising climate development: solar-electricity prices dropped by 89%, making it cheaper than fossil-fuel-based alternatives.

» The bottom line is that no industrial policy in the world can create sufficient substitutions for Chinese imports in the timeframe dictated by climate change. «

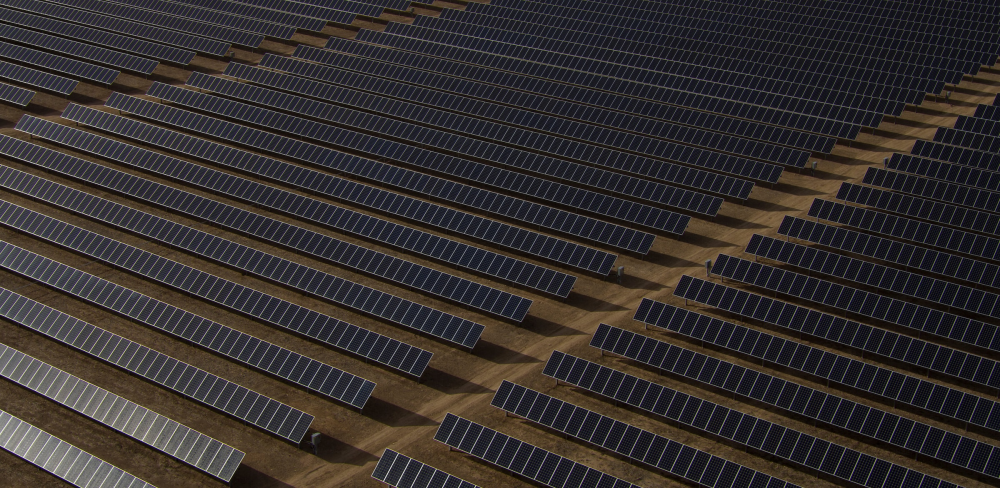

The downside: Germany depends on China to reach its 80% renewable energy goal by 2030. According to the German Economic Ministry’s new solar strategy, added annual capacity must increase from 7.2 gigawatts in 2022 to 22 gigawatts within a few years. At the moment, 95% of solar panels are imported from China, which has already threatened export limits on solar technology in response to the IRA and CHIPS Act. This certainly justifies diversifying supply chains for renewables, including batteries and critical minerals. However, the bottom line is that no industrial policy in the world can create sufficient substitutions for Chinese imports in the timeframe dictated by climate change.

Keeping the abovementioned maxim in mind, how Berlin invests in its Zeitenwende could still help lessen climate risks. Increasing security autonomy will partially insulate Germany and Europe from US pressure to decouple. And the clock is ticking, as US-Republicans have already started beating the drums on ‘German free-riding.’

Greening the Bundeswehr could also provide multiple climate benefits: Bayer et al. convincingly outline how doing so would not only accelerate domestic decarbonization, but also make the armed forces more resilient and independent on a logistical and operational level. A green Bundeswehr would also position Germany to credibly push for the inclusion of global military emissions (around 5%) under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. While only a small step, it would at least give global recognition to the relationship between security competition and the fight against climate change.

Because Germany’s influence is limited, its politicians and policymakers must pragmatically pick their battles amidst the trade-offs and opportunities that the increasing linkages between climate and security politics entail. That a new Cold War could spell the end of all hopes to limit global warming to 1.5 or 2 degrees should be the starting point for such calculations.

Ole Adolphsen

PhD Student, Johns Hopkins University

Keep on reading

In a Globalized World, No Security Without Climate Security

Because they are driven by narrow concepts of security, security strategies typically end up looking for answers to new threats in the same old places. But Germany still has a chance to do it differently.

National Security Means Addressing the Climate Crisis

When it comes to national security, the climate crisis is just as – if not more – threatening than traditional concerns like conflict and war. How can Germany embrace climate action?

Securing Supply Chains for the Low-Carbon Economy: The Case of Electric Batteries

The transition to low-carbon technologies is creating new dependencies for the European economy. Especially critical for Germany: electric batteries. To reduce risks and reshape emerging global value chains, Berlin and other EU governments must prioritize a comprehensive governance approach.