Strategic Ties, Not Blocs: Why Germany Should Promote a Multipolar Order

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz speaks during a press conference at the 2022 G7 summit at Elmau Castle in Kruen, Germany. (CLEMENS BILAN/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock)

Instead of joining those who invoke a new Cold War and decoupling from autocracies, Berlin should follow the vision of a polycentric world. Doing so will require a new approach to economic globalization.

The concept of interdependence is undergoing a fundamental revision in Germany. For almost three decades, interdependencies had been seen as a driving force for peace, as a means to universalize liberal norms, as an enabler for access to markets and raw materials and a stabilizer of global value chains, and – of course – as an argument to legitimize the supply of cheap Russian gas. Since Russia’s renewed invasion of Ukraine in February this year, Germans seem to have realized that asymmetric interdependence hardly differs from dependence.

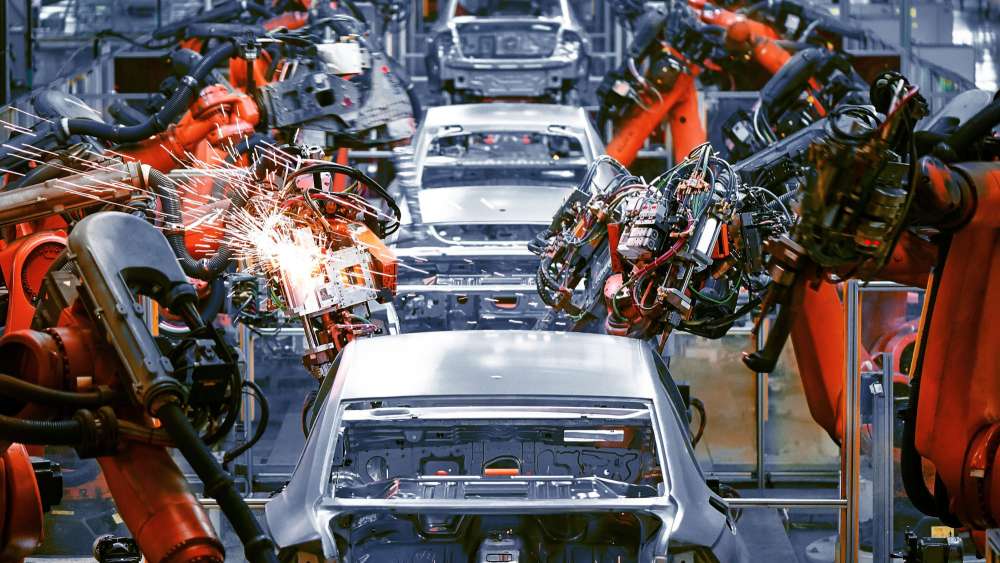

The large share of Russian gas in Germany’s energy mix, the importance of Chinese demand for German cars, machinery and chemicals, China’s weight as a supplier of important commodities and resources: these entanglements would be unproblematic only if both Moscow and Beijing operated according to the same political and socio-economic rationality as Germany – and if they prioritized the well-being of their own people over political ambitions.

Key Points:

- A decoupling from autocracies would spell considerable welfare losses for Germany. And global challenges like climate change or food insecurity will be harder to solve in a bipolar world.

- Germany should work to bolster the EU’s ability to act externally and with strategic sovereignty, including by strengthening EU defense capabilities and pushing for majority voting in EU foreign policy.

- Germany’s approach to economic globalization should put more emphasis on resilient value chains, the diversification of markets, on near-shoring of investments, and on due diligence.

Great Power Rivalry and Systemic Antagonism

Two macro trends form the undercurrents of this re-evaluation of interdependence. First, competition between major and regional powers – for spheres of influence, technological supremacy, control of markets, trade routes, and strategic raw materials – is intensifying. In other words, we are witnessing the re-emergence of classic great power rivalry. For a long time, it seemed that this rivalry would be fought out mainly through economic coercion, the setting of norms and standards, the manipulation of public opinion, and other means of hybrid warfare. The main opponent of the West, and first and foremost of the United States, appeared to be China. Beijing’s economic pressure on ‘misbehaving dependents’ like Australia and Lithuania, its Belt and Road Initiative, the controversy over the introduction of 5G network components by Chinese manufacturers, and strategic business take-overs by Chinese companies all reinforced this perception.

However, it is mainly Russia which has attempted to manipulate elections in the US and Europe, including by spreading disinformation and supporting European radical populists. China’s approach, on the other hand, has been far more subtle. Similarly, it is Russia which has repeatedly reminded us that the new great power rivalry will not exclude the recourse to violent means. While the wars in Chechnya, Georgia, Syria, Libya, and Eastern Ukraine already indicated this shift a while ago, Russia’s massive use of military force against Ukraine represents an epochal change in this regard.

» China would not become just another success story of universal liberalism. Instead, its leadership was determined to maintain and further consolidate its absolute control over the country’s society and economy. «

The second trend is closely interwoven with the first one and further reinforces it: the growing systemic antagonism between autocracies and democracies, or between police states and the rule of law, collective obligations and individual rights, state capitalism and market economies. This trend, too, has been looming on the horizon for several years. So far, it has manifested itself primarily in the growing contrast between China and the US. The 19th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in 2017 conveyed a clear signal: China would not become just another success story of universal liberalism. Instead, its leadership was determined to maintain and further consolidate its absolute control over the country’s society and economy.

Over the past years, Russia has also attempted to normatively elevate its imperialist policy, by casting itself as a socially conservative society rooted in traditional religious and family values – one that is superior to what Russian leaders and media have portrayed as an increasingly decadent, effeminate and permissive West. This systemic antagonism on normative grounds is increasingly condensing in the form of competing, if not conflicting fora: the Alliance for Democracies versus the Group of Friends in Defense of the Charter of the United Nations, or the G7 versus the BRICSplus, to name only a few.

The Perils of a Bipolar Order

Some deduce from these two trends that the world is heading for a renewed phase of bipolarity, even a Cold War 2.0. Unsurprisingly, this impression is particularly strong in Europe, where it is hard to imagine how a new confrontational, bipolar security order can be prevented as long as Russia continues its violent conquest and illegal occupation of Ukrainian territory. In the rest of the world, such a scenario seems far less likely, but it is not necessarily unpopular. An increasing number of politicians and analysts, especially in the US, seem to believe that it is high time for democracies to challenge and confront autocracies while the former are still in a position of ‘superior’ power, and to isolate the latter economically and technologically through decoupling. These calls not only neglect or miscalculate the detrimental effects of a new bipolarity, they also partially ignore reality – in several respects.

» A revival of global political competition between two blocs would make it more difficult to tackle pressing global challenges such as climate change, pandemics, food insecurity, and economic development. «

First, a revival of global political competition between two blocs would make it more difficult to tackle pressing global challenges such as climate change, pandemics, food insecurity, and economic development. Some seem to assume that the enlightened self-interest of countries like China and Russia alone could bridge the new cleavage and would suffice as a basis for cooperation with the West in these fields. But as China’s withdrawal from bilateral talks with the US on climate change already signaled: this hope might be an illusion.

Secondly, a new bipolar order would also mean considerable welfare losses for Germany, a country whose prosperity largely depends on worldwide economic entanglement – in other words: on globalization. The competitiveness of German companies very much relies on global value and supply chains as well as on access to energy sources and raw materials, which are mostly concentrated in countries that are not necessarily democracies. Similarly, the wealth of the German society depends on exports to fast-growing and non-saturated markets. Again, most of these markets hardly qualify as democratic. Still, an economic withdrawal from these countries would seriously undermine the central pillar of Germany’s political power: its economic strength.

Toward a Polycentric World Order

Thirdly, the clear distinction between ‘democracy’ and ‘autocracy’ is an artificial one. The range of political systems between the poles of Switzerland and North Korea is wide, as is the grey zone in which illiberal, merely electoral democracies coexist with liberal and open autocracies. And the normative ‘split’ between liberalism und authoritarianism also manifests within established democracies like the US, France and Italy – not to mention Poland and Hungary.

» The clear distinction between ‘democracy’ and ‘autocracy’ is an artificial one. The range of political systems between the poles of Switzerland and North Korea is wide. «

Finally, a large part of the world refuses to choose between these two camps. This became obvious in the recent voting behavior of many states in the UN Security Council and General Assembly and in their unwillingness to support US and European sanctions against Russia. Many countries that the West regards as democracies and ‘natural’ partners – among them India, Brazil and South Africa – have resisted pressure to clearly position themselves against Russia. They see this pressure as another expression of Western arrogance, hypocrisy and double standards. It is also not yet clear whether China would even opt for forming a new bloc with other autocracies, or if it would enter into a strategic alliance with Russia. Maximizing its own strategic autonomy seems to be Beijing’s more plausible preference.

Instead of joining those who invoke a new bipolarity and decoupling from autocracies, for which the newly popular “friend-shoring” is just a more friendly term, German foreign policy should be guided by and actively promote the vision of a multipolar – or polycentric – world order. Three core elements would characterize such a foreign policy.

A New Approach to Globalization

First, Germany should focus on the output legitimacy of the European Union and its ability to act externally, meaning, to achieve strategic sovereignty. The success of the Next Generation Fund, the revision of the EU’s treaties and structures, the strengthening of the Union’s own defense capabilities, and the shift to majority voting in its foreign policy are all central prerequisites for this.

Secondly, Germany should acknowledge that other systems are difficult to change from the outside yet still important players to interact with. It is therefore necessary to design interfaces for political, economic, social and cultural transactions with these systems. Bilateral relations with any country outside the EU should be determined by an appropriate mix of cooperation, competition and confrontation, also known as compartmentalization. In addition, other countries, especially like-minded ones, should be won over for strategic partnerships and alliances. This, in turn, requires an understanding of their motives, interests and normative settings as well as a willingness to make attractive material and immaterial offers to them.

» Bilateral relations with any country outside the EU should be determined by an appropriate mix of cooperation, competition and confrontation, also known as compartmentalization. «

Last but not least, such a foreign policy can only succeed if the business model of German companies undergoes significant adjustments. Most of them are realizing that their dependence on a small number of suppliers and markets as well as their focus on economies of scale, specialization and efficiency – the very basis of their competitiveness and business success, so to speak – can carry significant risks in a world shaped by great power rivalry and systemic competition. Sudden political shocks, economic coercion, epidemics and natural disasters can put an immediate end to market access and supplies. We therefore need a new approach to economic globalization, one which puts more emphasis on the resilience of value chains, the diversification and regionalization of markets, on near-shoring of investments, and on due diligence.

Stefan Mair

Director, German Institute for International & Security Affairs (SWP)

Keep on reading

War and Unpeace: The Dangers of Connectivity

The age of peace is over. The culprit: global connectivity. Why the connections that knit the world together are also driving it apart – and what this means for Germany’s security policy.

Reality Check on China: Protecting Europe’s Science and Technology Potential

Many European states believe that they are no match for China. But as the French example reveals, this perception may be false. It is high time for Europe to take a realistic look at its dependencies and assets vis-à-vis China – especially in the field of science and technology.