Another Undeclared Conflict: Economic Statecraft and Germany

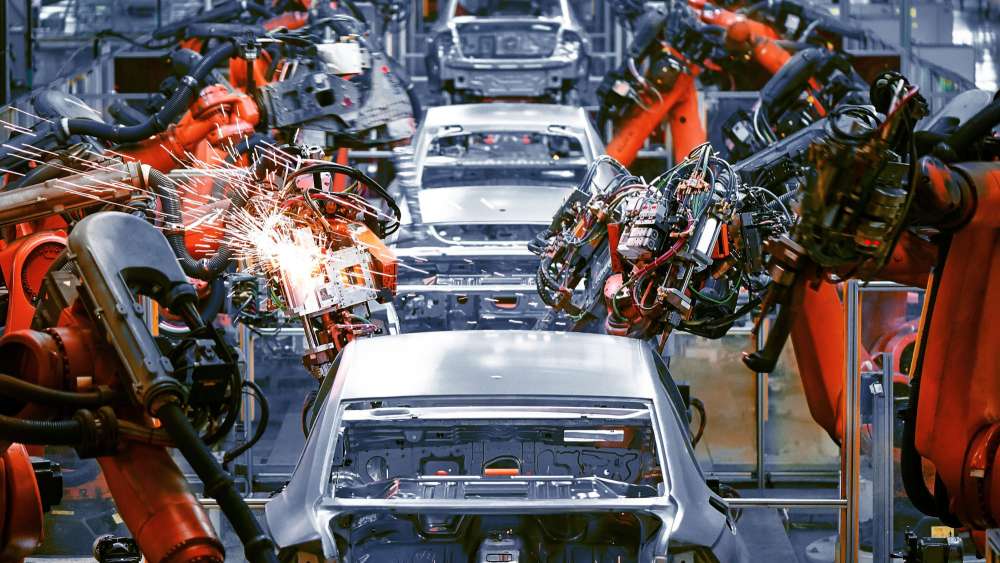

(Gerken Ernst/imageBROKER/Shutterstock)

Economics and finance will determine the balance of power between states in the decades to come. Germany should recognize its own sway in this regard – and recalibrate its approach to using economic tools in foreign policymaking.

No one has written a conclusive book on the art of economic war, and yet the events of this year demonstrate that it is being waged. How Germany chooses to frame its financial and economic leverage will be instructive for global standard-setting and the role of economics in foreign policy — and for the foreseeable future.

But first, what exactly is economic statecraft? The most concise definition might be: the intervention by sovereign governments into the behavior and actions of private industry on stated national security grounds. Or formulated as a question: When, and under what circumstances, does a state, through law, limit — or explicitly expand — commercial activity to achieve a foreign policy goal? Putting clear bookends on such policies — in other words, determining what national security is and what it is not — is fluid in theory and practice. The only rules of engagement that economic statecraft currently upholds for those deploying it are the varying levels of pain tolerance for commercial or financial blowback.

» Sanctions, export controls, investment screening, trade tariffs, financial market restrictions—these are all tools used by governments and regulators with the explicit objective to curb a foreign actor by limiting their commercial activity. «

Let’s start with some examples of economic statecraft as foreign policy that are clear-cut: decisions by the P5+1 P5+1 and partners to restrict commercial activity with Iran to compel negotiations over the country’s nuclear program; export controls on goods to Russia that support Moscow’s aggression in Ukraine; choices by countries such as the UK or the Nordics to exclude Chinese technology providers from supplying components for 5G networks due to concerns over data collection and espionage. Sanctions, export controls, investment screening, trade tariffs, financial market restrictions — these are all tools used by governments and regulators with the explicit objective to curb a foreign actor by limiting their commercial activity.

Key Points:

- There is a problematic disconnect between the design of economic measures for foreign policy objectives by policymakers and their execution by the private sector.

- The line between economic foreign policy and protectionism is increasingly blurry. Berlin should recognize that its strategic playbook no longer holds – and rethink its approach to economic statecraft.

- Germany’s upcoming security strategy should: define a doctrine for wielding the tools of economics in foreign policymaking; determine the line between foreign and industrial policy; and point the way toward a new set of norms and standards for finance and regulation.

A Crucial Disconnect

Governments can use these tools as placeholders for military confrontation or if they judge that the challenge at hand is best addressed not through physical force but by coercion through the fine plumbing of international financial systems and supply chains. Yet despite the Western bazooka of economic measures unleashed against Russia since the February 24 invasion of Ukraine, discussions of economic statecraft within European security and foreign policy circles remain theoretical. To this day, major security convenings do not feature finance as an element or instrument of foreign policy.

Why is this? Shouldn’t foreign or defense ministers be fluent in the lingo and substance of banking regulation by now? One explanation is that the technocratic links between these fields simply aren’t strong enough. In the United States, in Germany and even within the EU’s institutions in Brussels, the bureaucratic ability to implement economic statecraft feels much more like untangling thousands of incompatible charging cables than executing financial command-and-control, as much as one would like to believe that a sanction is something efficient. Similarly, the media like to report that Europe has “slapped” sanctions on Russia, as if the task were done once there is a press release.

» The bureaucratic ability to implement economic statecraft feels much more like untangling thousands of incompatible charging cables than executing financial command-and-control. «

There are two main reasons for this disconnect (although we could easily come up with more). First, the circles of individuals who might understand the interplay between nuclear deterrence and global capital markets are understandably small. Academic training and pigeonholing churn out specialists, not interdisciplinary thinkers. Second, it is the private sector that bears the burden of executing economic measures: whether the Kremlin loses access to high-end component parts or can only sell oil under the conditions of a new price cap is the responsibility of exporters and shipping companies, not government ministries. In other words, the distance between policy design and execution is uncomfortably wide.

From Foreign Policy to Domestic Competitiveness

The war in Ukraine has forced a caesura in economic relations between Europe and Russia, with cascading effects on global energy and commodities markets. The speed and intensity of Russia’s economic ouster far surpasses any previous deployment of economic pressure against any country, and it will probably take a decade to understand its full ramifications. Yet, almost simultaneously, governments big and small are starting to use these same instruments to support another concept of security, namely, to defend their countries’ domestic economic welfare and international competitiveness. China’s aggressiveness against foreign firms, regulatory tightening and predominance in key areas of emerging technology, combined with supply chain disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, have forced open, free-market systems to consider unprecedented measures to preserve their place in the global economic food chain.

» The speed and intensity of Russia’s economic ouster far surpasses any previous deployment of economic pressure against any country, and it will probably take a decade to understand its full ramifications. «

The best example of this is trend not sanctions, but export controls, which still get too little attention in public discourse. Export controls on dual-use goods, for instance, prevent nuclear proliferation and chemical weapons attacks; as stated, they are also currently preventing Russia from deploying state-of-the-art materiel in Ukraine. But the Biden administration’s recent measures to block Chinese access to Western components for chips and emerging technologies through the novel Foreign Direct Product Rule is a hybrid of the two: they aim to prevent China from developing advanced systems that could have military applications – but they also intend to slow the growth of China’s indigenous industry to the advantage of the United States and perhaps its partners, given the far-reaching implications of the regulation. At the same time, both the US and EU have widely subsidized their domestic chip industries. Export controls, therefore, are not only a tool of foreign policy but of industrial policy: they help to pull advanced technological development under the umbrella of the military-industrial complex and spur economic growth.

Germany’s Special Role

Germany is both uniquely powerful and uniquely vulnerable when it comes to shifting patterns in how governments direct economic behavior. German policymakers often portray themselves as squeezed in between two major markets that are increasingly unpredictable. And surely no one will deny that both China and the United States can be unpredictable. But this self-depiction is just not accurate. Germany is the fourth-largest economy in the world. Its choices have global ramifications in trade and for fiscal and monetary (im)balances. Together with the market and regulatory sway of the European Union, Germany is a great power.

» German policymakers often portray themselves as squeezed in between two major markets that are increasingly unpredictable. But this self-depiction is just not accurate. «

At the same time, the complex global web of regulations makes governance operationally difficult. The use of economic tools for foreign policy goals closes markets and invites retaliation, often asymmetrically. The increasingly blurry line between foreign policy and protectionism threatens a longstanding German strategy to ensure its model of national welfare through relatively inexpensive industrial production at home paired with the long arm of German corporations generating gross national wealth overseas. Russia’s war, China’s aggression and the specific interests of many global actors have upended the playbook for Germany and its partners. Which begs the question: What now?

The development of its first-ever National Security Strategy is a starting-off point for Berlin to calibrate its approach to economic statecraft. Three considerations can help:

- Define a doctrine for wielding the tools of economics in foreign policymaking. The technocratic tools of economic statecraft have defined the West’s ability to undermine Russia’s war in Ukraine, and this year’s events have unleashed a debate over Germany’s military-strategic culture. Now the same conversations must happen for the use of financial and economic tools, both at a domestic level and in Brussels, where many policies are set. What will be the relative burden of regulatory measures for handling geopolitical adversaries? What are the capabilities and limitations of each tool in the toolbox? And how will each be integrated into the organizational design of German decision-making?

- Determine where foreign policy ends and industrial policy begins. To be fair, no capitalist country knows where the line is. The greater the proportion of national industry and economic production that depends on state subsidies or non-tariff barriers to remain competitive, the greater the risk that resources are allocated inefficiently and market failures are papered over. Moreover “two-fers” like export controls on chip production send mixed messages, especially to autocratic leaders. Is the West implementing controls because of what China does in Xinjiang or the South China Sea (foreign policy), or because China has become too industrially competitive for Europe’s and the US’ comfort? That being said, the survival of certain industries are likely critical to maintaining domestic stability, and in times of supply chain and commodity disruptions, governments could argue that trade policy and economic growth are indeed matters of national security. Ultimately, Germany as an export-oriented powerhouse will likely face tough decisions in the coming years as to how much the government will engage to sustain its industrial competitiveness. And the tools of economic statecraft will define the government’s range of motion.

- Do not be afraid of setting standards. Given the country’s centrality to the European economy and far beyond, the choices that both the German government and its industry make will have — and should have — potentially global ramifications. Now is the time to lead the way toward a new set of norms and standards for finance and regulation, one that is imbedded within fast developing EU frameworks, and to do so together with likeminded international partners.

The most rapidly developing and exciting areas of international security lie outside the concentric circles of traditional security decision-making and dialogue. We need to fix this. Economics and finance will determine the balance of power between nations in the decades to come. Decisions Germany makes in the commercial and regulatory realm will matter just as much as its policies toward territorial defense and hard power.

Julia Friedlander

CEO, Atlantik-Brücke & Co-Founder, Economic Statecraft Initiative at the Atlantic Council in Washington

Keep on reading

Germany and the EU Need to Keep Engaging with China

History teaches us that a decoupling from China will likely backfire. Without Beijing, efforts to solve key global issues will not succeed. Germany should focus on avoiding over-dependencies on China – not abandon ties altogether.

Reality Check on China: Protecting Europe’s Science and Technology Potential

Many European states believe that they are no match for China. But as the French example reveals, this perception may be false. It is high time for Europe to take a realistic look at its dependencies and assets vis-à-vis China – especially in the field of science and technology.