“The Ukraine War Has Clearly Changed the Very Notion of Energy Security”

(Nicholas Doherty/Unsplash)

Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has altered the geopolitics of energy. Going forward, energy security will be determined by how swiftly states manage to shift to a low-carbon economy.

The past year has brought a lot of turmoil in global energy markets. Russia’s renewed invasion of Ukraine and subsequent Western sanctions against Moscow, one of the world’s major exporters of natural gas and oil, suddenly upended key international supply structures for energy. What do you make of the state of the global energy system today, more than one year on from that moment of rupture?

We have been witnessing a fundamental shift in the geographies of world energy. Russia, a key actor in the global energy economy, left the European market. When it comes to natural gas, Moscow chose to do so by cutting off its supplies; in oil, it was forced to seek customers elsewhere as its exports were sanctioned by the EU, the US and the G7. As a result, Russia’s energy exports have been re-directed east, with emerging market economies like India establishing themselves as important new customers in oil. The EU’s import structures, on the other hand, have to a large degree shifted westward, as American Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) became crucial in replacing Russian piped gas. Russia is now actively seeking Asian export markets also for gas, so this pattern is likely to deepen. This not only testifies to the new geopolitics of energy but also increases Moscow’s risk to develop lopsided trade dependencies with only few major consumers, including with China.

At the same time, Western sanctions ended up further eroding the dollar dominance in oil markets. Russia’s new customers, notably India, pivoted to Middle Eastern currencies and the ruble to settle payments. Should other emerging economies go down a similar route, the global crude oil market may see a slow ‘Balkanization’ – it will become more fragmented. What is more, Western nations are doubling down on their decarbonization targets. This will pay off in the medium term. The years ahead, however, may see a bumpy transition from a fossil-fueled to a non-fossil world, and corresponding volatility in terms of prices.

The flipside of talk about an energy crisis is the need for energy security. European governments and Germany’s in particular have had to prioritize rapid-response measures to make sure their core energy needs are still met. The global consequences of this upheaval, including for low- and middle-income countries in the Global South, have received less attention. What do we know about those?

The energy crisis did of course not stop at Europe’s borders. Energy markets are highly globalized and interconnected. What happened in the market for LNG drives this point home: as Europeans eagerly contracted LNG to replace Russian gas, they ended up pricing others out of the market. Particularly middle-income countries suddenly found it hard to secure their gas supplies as EU hub prices hit record highs of 300 euros per MWh – 15 times more than the pre-war levels. LNG supplies are rather inflexible in the short run, so Europe’s shopping spree amounted to a zero-sum game in which financially weaker economies lost out. Pakistan is an example, and so is Bangladesh. Other South East Asian nations, too, saw blackouts, dwindling forex reserves and suffering economies. What soaring energy prices do at home is also what they do at a global level: they hit the most vulnerable the hardest.

» What soaring energy prices do at home is also what they do at a global level: they hit the most vulnerable the hardest. «

How will the developments of 2022 impact the green energy transition and global action on climate change? What should we expect in this regard over the coming years?

If there is anything positive coming out of the 2022 events, it is that the energy transition clearly has gained speed. Public money is being poured into efforts to really change gear. Major policy initiatives, including the European Union’s REPowerEU program and its Net Zero Industry Act as well as a flurry of national-level policy measures, are all meant to rapidly bring down the share of fossil fuels in the energy mix and to decarbonize production. The Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act – though not primarily motivated by Russia’s aggression – will help clean up US manufacturing and mobility. The International Energy Agency even goes so far as to suggest that the Ukraine war is “turbocharging the clean energy transition.” I concur with this assessment.

The past years has also revealed once more how swiftly geopolitical changes can alter supposedly fixed economic realities. How will conventional and energy security intersect in the near future?

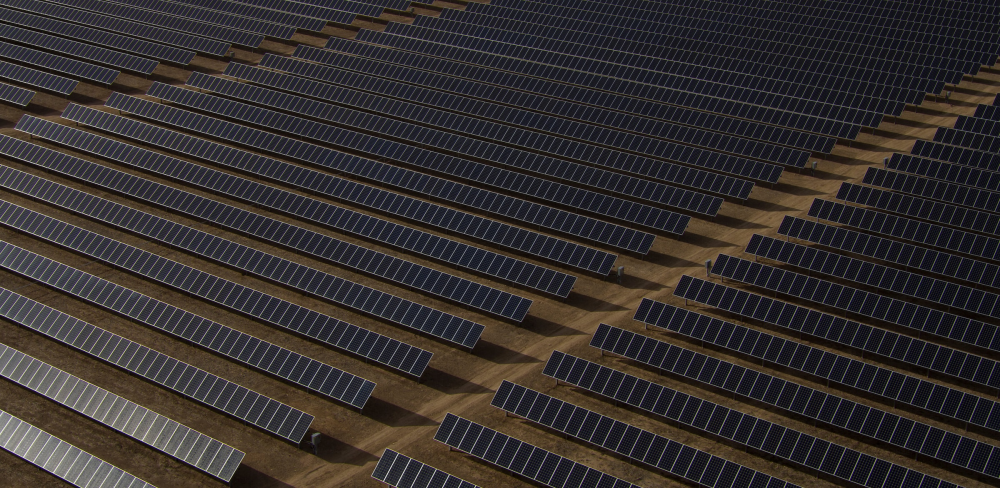

Energy security concerns will always drive governmental action, and states will mobilize what they have to ensure industry and households are well-supplied at affordable prices. In Europe, this has meant, among other things, pledging some 800 billion euros in public money to buffer the impact of high energy costs resulting from Russia’s aggression – a staggering number. However, firefighting is one thing; the other is to ensure greater resilience to shocks going forward. Here, the Ukraine war has clearly changed the very notion of energy security. Diversification now includes pivoting to non-fossil sources, and governments are acutely aware of the security premium coming with renewable energy sources – which are ideally home-grown or, for the most part, supplied from closer to home. Renewables have become securitized, that is, they are now part of the domain of high politics. This allows governments to use extraordinary measures for fostering them – from fast-tracking permits for off-shore wind farms to enhancing strategic grid infrastructure through state aid. To a large extent, energy security will now be determined by how quickly countries manage the shift to a low-carbon economy.

» Renewables have become securitized, that is, they are now part of the domain of high politics. «

In your view, what role – if any – will multilateral organizations have to play in global energy governance going forward?

The one clear trend we are observing at the moment is the one toward more public intervention. A case in point is the EU: for more than two decades, energy policies followed the liberal script. Policymakers sought to integrate energy markets and make them competitive. Now, the bloc is setting up a joint gas purchasing vehicle – effectively a buyers’ cartel. It has also capped gas prices and is pondering a more restrictive market design. All the while, EU member state governments are nationalizing key energy providers, including EdF, UNIPER or VNG. The talk of the day is less about multilateralism and open international trade. Instead, it is about strategic partnerships to enhance supply chains, and about exclusive alliances of the likeminded – whether in raw materials (which the EU wants to secure, among other measures, through a so-called Critical Raw Materials Club) or in fighting climate change (for instance, by way of setting up a G7 Climate Club).

Clean energy solutions are no longer a matter of global economies of scale. They are now a matter of strategic industrial policy. Clearly, we are entering an era where the state is back in determining who trades with whom and on which terms. This holds true more broadly and not just in the energy domain. To some extent, we are simply going back to where we came from: energy companies will end up following the flag again. In the old days, this was mainly about oil. Now it is about strategic minerals, clean technologies and who has the competitive edge in a decarbonized world going forward.

Andreas Goldthau

Director, Willy Brandt School of Public Policy, University of Erfurt

Keep on reading

Climate Politics and the New Cold War

In the looming ‘new Cold War’, climate and security concerns cannot be separated. As Germany reconfigures its security policy, how can it minimize the effects of great-power competition on a deteriorating climate?

Securing Supply Chains for the Low-Carbon Economy: The Case of Electric Batteries

The transition to low-carbon technologies is creating new dependencies for the European economy. Especially critical for Germany: electric batteries. To reduce risks and reshape emerging global value chains, Berlin and other EU governments must prioritize a comprehensive governance approach.

Shock-Proofing Global Food Systems: A Pathway to Peace, Security and Prosperity

Efforts to enhance global food security are a remedy to several causes of global insecurity at once. Germany should invest in agricultural innovations that benefit small-scale farmers, starting with better support for neglected crops.