Security through Preparedness: Lessons from Australia and the Indo-Pacific

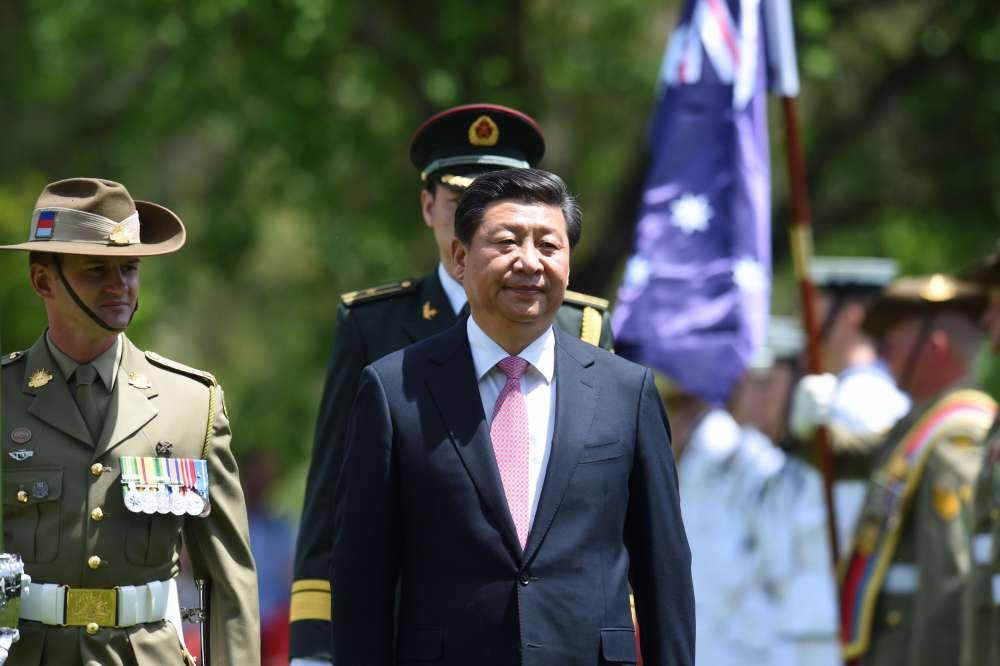

Photo: Lukas Coch/EPA/Shutterstock

For any country with strong stakes in a rules-based order, China's recent aggression in the Indo-Pacific should set off alarm bells. It's time for new thinking about national preparedness – as Australia has learned in recent years.

Key Points:

- Germany can learn a lot from the sea change in Australia’s China policy.

- Regional or internal shocks quickly become global – so it is essential to plan ahead.

- In its response to China, Germany should apply its economic leverage.

Amid intensifying global strategic competition, the National Security Strategy will need to prepare Germany and Europe for growing risks in and from the Indo-Pacific region.

Why? The Indo-Pacific region is now the center of gravity in the global system in terms of economics, security, demography, and long-term risks – whether from interstate conflict or the impacts of the climate crisis.

This globally connected region is also where China’s rising power and assertiveness most sharply intersect with the interests and values of others – not only those of Indo-Pacific nations like Japan, India, South Korea, the states in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and Australia, but also of all global stakeholders in a rules-based system. Thus, European security cannot be considered in isolation from the future of the Indo-Pacific.

In recent months, Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine has understandably concentrated Germany’s security focus on the European continent. However, the conflict will develop within a global context, which will be framed by the China-Russia ‘no limits’ partnership and the lessons Beijing is learning and will apply for its own purposes of dominance.

It is not up to an Australian analyst like myself to tell European governments how their foreign and security policies should look. However, it may be useful to share insights from the Australian experience of adjusting our own strategic settings to cope with a world of power rivalry and authoritarian assertiveness.

Chinese Coercion in the Indo-Pacific

Like Germany, Australia is a successful liberal democracy: a federation that is home to diverse voices and cultures, where people value their freedoms while also practicing pragmatism in the pursuit of prosperity and a high quality of life. That is why it is interesting to note that, in recent years, our people and our politics have come to terms with uncomfortable new realities, thus preparing the nation to be more resilient in the years ahead. This process has been reluctant but irreversible.

Australia’s political discourse has shifted significantly. Now, our newly elected center-left government is a champion of national security, and is further redefining the concept to incorporate climate policy and social inclusion as well as the protection of our interests and values. The current German policy debate – on both Russia and China – reminds me of Australia’s debate in the years between 2016 and 2018, which marked the start of our ‘reality check’ regarding China.

Up until that point, the popular political wisdom in Australia had been that we could gain enormous economic benefits from trade relations with China without incurring significant security risks. Some major industries – notably iron ore, coal, agriculture, seafood, education, and tourism – had already developed a heavy reliance on the Chinese market, but many of their decision-makers preferred to ignore the potential downsides.

The blithe assumption – especially in the business community – was that we would never be forced into hard choices. China would remain sensible, reform-minded, and would gradually liberalize and become conscious of its stake in a stable, peaceful status quo – even while modernizing its military and making nationalist noises.

A series of dramatic developments changed all of that, jolting us awake. Under President Xi Jinping, China’s stance shifted, moving to hard-line authoritarianism and even verging on totalitarianism. We have all read about China’s chilling treatment of the Uyghur people and the crushing of once-promised freedoms in Hong Kong. Absolute control by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) domestically was mirrored by a more reckless assertiveness abroad: not only in China’s maritime periphery, but also across our two-ocean region, where Beijing wielded its security presence and corrupting political influence in many vulnerable states across the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

China’s armed forces – which include a rapidly strengthening army, navy and air force, plus the coast guard and other paramilitaries – began to push harder on many fronts. Threats and confrontations have escalated against ASEAN countries in the disputed South China Sea, against Japan in the East China Sea, violently against India at the contested land border, and especially against Taiwan. Even Australian forces have found themselves challenged by Chinese forces in reckless encounters at sea, including within our own Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

It has become clear that Xi Jinping’s regime is willing to jeopardize regional and global peace and prosperity in order to tighten political control and pursue strategic primacy in the Indo-Pacific region – while also rivalling the United States on a global stage.

And in Australia? Our intelligence services, free press and civil society institutions have all grown increasingly concerned about the CCP’s interference and influence activities on our soil. These intrusions are aimed at eroding our sovereignty, weakening our alliance with the United States, silencing Australia’s independent voice as a champion of international law in the South China Sea, and intimidating the diverse communities of Chinese origin among the Australian population.

» Xi Jinping’s regime is willing to jeopardize regional and global peace and prosperity in order to tighten political control and pursue strategic primacy in the Indo-Pacific region. «

A Shift in Canberra’s China Policy

In response, there has been a sea change in Australia’s security and foreign policy posture over the course of a number of years. This process is far from over: in particular, strengthening our defense forces to increase their strike capability remains a work in progress. And there is an ongoing, robust national security and foreign policy debate across the Australian political spectrum, such that these issues featured prominently in the run-up to our 2022 elections.

Still, much of the hard work has now been done to make our nation more prepared against Chinese aggression, an effort that has drawn support from across Australia’s major political parties and the majority of public opinion.

None of Australia’s actions were aimed at offending China, even if Beijing’s propaganda was quick to portray it that way. The point was to build up national self-protection mechanisms. A long-term relationship of mutual respect can only begin with self-respect at home.

Tough legal protections have been put in place to safeguard critical infrastructure, with close scrutiny of the risks stemming from foreign ownership or control. Laws were introduced to criminalize foreign political interference, which require transparency from former politicians with foreign links, ban foreign political donations and allow the Australian federal government to stop state governments from conducting international deals (such as Beijing-drafted Belt and Road agreements) that undermine national interests.

Our international diplomacy was reshaped to help established the so-called Quad, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue – a strategic security partnership between Australia, India, Japan, and the United States. Australia has also focused on a stronger alliance with Washington, including the AUKUS agreement – an advanced technology-sharing arrangement between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States – which enables Australia to acquire nuclear-powered submarines. This decision broke established anti-nuclear taboos among the Australian people, and yet it was widely supported – a sign of how much things have changed.

In our Pacific neighborhood, in which China has rapidly expanded its influence, we are stepping up support for vulnerable democracies through development initiatives, infrastructure projects and investments in education and governance. We will not be able to do this alone and hope for a wide range of development partners, including from Europe.

Australia’s growing security engagement with Europe – including by providing military equipment to Ukraine and attending the NATO summit as an Indo-Pacific partner – is another signal that we recognize the need for solidarity with democratic partners around the world.

The Indo-Pacific and European strategic dramas loudly echo each other and offer crucial lessons to be learned. Kurt Campbell, who is the lead on Asia policy in the Biden administration, has argued: “These may be two theaters, but there’s one operating system strategically.” This is consistent with how Australia sees the challenge ahead.

The Australian Example of Countering China

Indeed, the Australian experience of preparing to face a more coercive China can serve as something of an early warning system for other democracies around the world. This is precisely why Beijing has concentrated much of its displeasure in recent years on Canberra, in the form of trade sanctions and a diplomatic freeze.

China’s concerns included Australia’s prudent decision to exclude Huawei from our 5G network and the outspokenness of our government which, in 2020, called for an international investigation into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic.

But Beijing’s bullying has failed. China is now resuming dialogue with the new government in Canberra, despite there being no substantial change in Australia’s China policy. Indeed, many of our industries – after suffering initial damage – have quietly diversified their markets, and the country is now more closely examining the security of our supply chains. All this confirms the logic of putting national security settings in place to prepare for tough times ahead.

Germany will draw its own strategic lessons from the disrupted and dangerous environment the world is facing. In Australia, we are now conscious that we cannot wish away the consequences of global shocks like COVID-19, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine or the prospect of future Chinese aggression against Taiwan.

Another learning: regional or internal shocks quickly become global. No one knows for certain how the China-Russia partnership will develop, or how Putin’s cruel strategic blunder in Ukraine will affect events in the Indo-Pacific in the years to come. But there is a significant likelihood that, at some point, China’s leadership will see a window for affronting action that could have a catastrophic impact globally. For any country with strong stakes in a rules-based order, this requires new thinking about national preparedness.

» There is a significant likelihood that, at some point, China’s leadership will see a window for affronting action that could have a catastrophic impact globally. «

Security Through Economic Leverage

The response to future security risks in the Indo-Pacific will not solely revolve around military power – far from it. And where it is about military power, the fundamental deterrent will remain the US’ capability and willingness to dissuade China and defend its allies. Here, the main difference that Europe can make will be in providing more for its own security, and thus enabling the United States to sustain – or even increase – its long-term focus on the Indo-Pacific.

In its response to China, Germany cannot afford to underestimate the geo-economic dimension: the use of economic leverage for strategic purposes. On a day-to-day basis, this means helping to build capacity in small and developing Indo-Pacific nations and providing alternatives for investment, infrastructure, technology, education, and development assistance so that these states are not primarily looking to China, which uses such ties to exert geopolitical control.

All nations also need to be prepared for the worst: as Russia is currently reminding us, bad dreams really can come true. As is the case with the invasion of Ukraine, Germany and Europe would rapidly feel the geopolitical and economic shockwaves of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. But China also needs Germany and Europe. For all countries who do business with China but want to maintain a stable international order, the challenge ahead will be to develop a national security posture which recognizes that we, too, have economic leverage – and that it is possible to use that leverage to deter future conflict.

Professor Rory Medcalf is the head of the National Security College at the Australian National University and author of the book, “Indo-Pacific Empire: China, America and the Contest for the Indo-Pacific”. He is a convener of the Australia-EU 1.5 Track Strategic Dialogue.

Rory Medcalf

Head of the National Security College, Australian National University

Keep on reading

Editors’ Note: A Strategy for the “World After”

In opinion pieces, interviews and debates, 49security will feature suggestions on how Germany can better position itself in a world that is rapidly changing. A few words on what is to come from your editorial team.

It’s the Politics, Stupid: Lessons for Germany from US Security Strategies

A successful national security strategy needs a solid political foundation. In democracies, that foundation – for better or worse – rests on the electoral process and the political leaders it produces.

Wanted: Klare Leitlinien für die zukünftige Sicherheitsordnung in Europa

Der russische Angriff auf die Ukraine hat gezeigt, dass es eine kooperative Sicherheitspolitik gegenüber Moskau nicht mehr geben kann. Die Sicherheitsstrategie muss neue Realitäten reflektieren – und die deutsche Gesellschaft auf die Kosten einstimmen.