Economic Zeitenwende? Lessons from Japan’s Economic Security Policy

(Roméo A /Unsplash)

Reducing its dependencies will be an important task for Germany’s first-ever National Security Strategy. Japan’s pioneering policy of economic security can offer a number of lessons for Berlin.

In his speech at the Asia-Pacific Conference of German Business (APK) on 13 November in Singapore, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz stated: “The current geopolitical environment calls for more resilience and for building greater technological sovereignty. We want to diversify our trade relations and strengthen our economic ties with the [Asia-Pacific] region.”

Scholz highlighted the risk of developing unbalanced dependencies, especially regarding critical technologies and supply chains. Reducing such dependence will be an important task for Germany as it develops its first-ever National Security Strategy. Japan’s pioneering policy of economic security can offer a number of lessons for Berlin.

Political Leadership and Institutional Adaptation

Japan has long benefited from China’s economic growth, but has become heavily dependent on Beijing as a market as well as a manufacturing hub and source of key resources and products. Tokyo’s dependence is not only on industrial products: Japan procures almost all of the 34 rare metals specified in its 2020 International Resource Strategy from abroad. Among them, more than 80% of all Tungsten (necessary for the production of special steels) and more than 60% of Fluorite (used for processing lithium-ion batteries and semiconductors) are produced in China. In addition, Japan imports 60% of its rare earth elements – which is required for electric vehicles, a field where demand has increased significantly – from China.

Beijing’s growing political assertiveness – particularly provocative Chinese actions in 2010 around the Senkaku Islands – has led Tokyo to decrease its dependence on China. As the examples of Australia and Lithuania confirm, Chinese statecraft does not shy away from using economic dependencies to deter other countries from pursuing policies that Beijing deems against its core interests. This is the crux of the economic security challenge posed by China.

Key Points:

- To combat Beijing’s growing assertiveness, Japan has strengthened its economic security policy – a tactic Germany would be wise to mirror in its National Security Strategy.

- Japan has established four key pillars of economic security and assigned ministerial responsibly to each sector, but a stronger government management role is still needed.

- Now is the right time for Berlin and Tokyo to engage in peer-learning on the best practices for economic security.

Against this background, Tokyo established Japan’s National Security Council (NSC) in 2014 and added an economic division to the National Security Secretariat (NSC’s Secretariat) in 2020, which leads Japan’s strategy on economic security (at the time of its inception, 20 of the 90 NSS staffers were reportedly members of the economic section). Subsequently, the Japanese Government created the brand-new post, Minister of Economic Security, and is preparing to establish a national think tank specializing in economic security. The institute is tentatively called the “Security and Safety-Related Think Tank Project”. Admittedly, it is not the most evocative name – but given that there are so few national policy think tanks in Japan, establishing this institution was an exceptional move. Other steps Japan has taken toward economic security include creating a new post, the Special Advisor on Human Rights to the Prime Minister, and founding a Business and Human Rights Policy Office within the Japanese Minister’s Secretariat of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI). The METI-led corporate human rights due diligence is one of the key topics of economic security in Japan.

This series of economic security-related policies was promoted under the Former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s fourth administration (2017−2020). In the early years, Liberal Democratic Party politician Akira Amari played an important leadership role in these tasks. Later, Takayuki Kobayashi, who in 2021 became the first Economic Security Minister at the unusually young age of 46, prepared the Economic Security Promotion Act (ESPA). The bill was passed by Japan’s National Diet in May 2022. In August 2022, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida appointed Sanae Takaichi, a prominent conservative politician, as the new Economic Security Minister in a cabinet reshuffle. Since Takaichi is known as a hardliner against China and has influence within the ruling party, this nomination was perceived as Kishida’s strong intention to promote economic security policies.

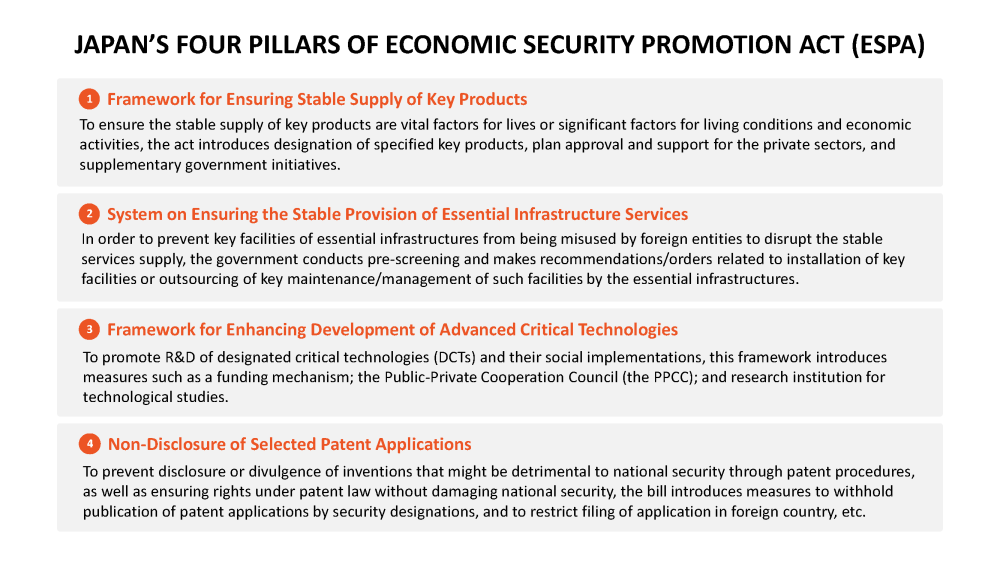

Japan’s ESPA consists of the following four pillars: 1) supply of key products; 2) critical infrastructure; 3) designated critical technologies (DCTs); and 4) non-disclosure patent system. The details of each pillar and the overall system can be seen in the graphic below.

Source: Koki Shigenoi /Nikkei, 21 October 2022

Japan’s governmental roles and responsible agencies for the four pillars can be summarized as follows:

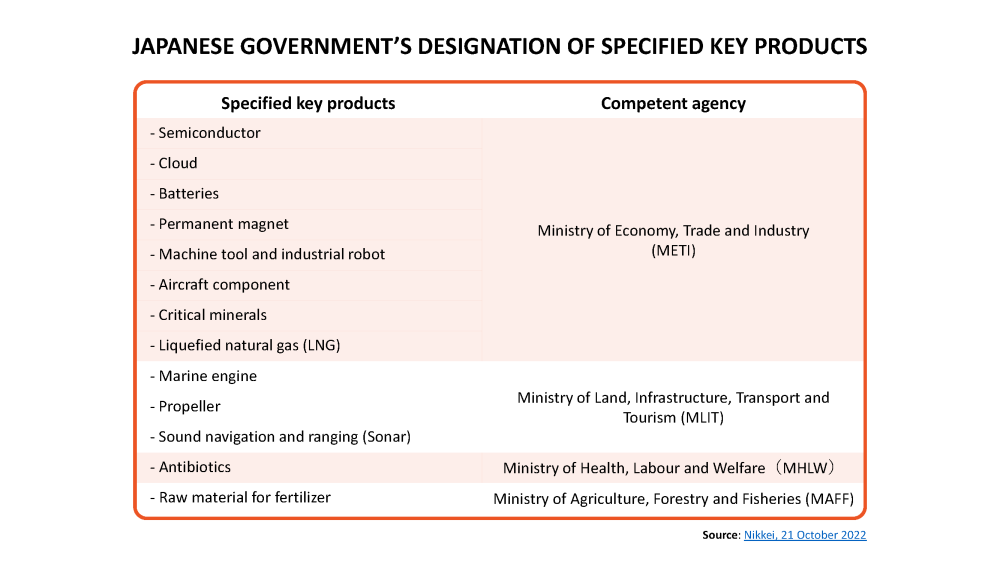

- First pillar (supply chains of key goods): The Japanese Government designates the specified key products and certifies and supports the approved plan submitted by companies, such as providing grants and two-step loans. Because the key goods are diversified across sectors, different competent agencies will be assigned according to the items in question.

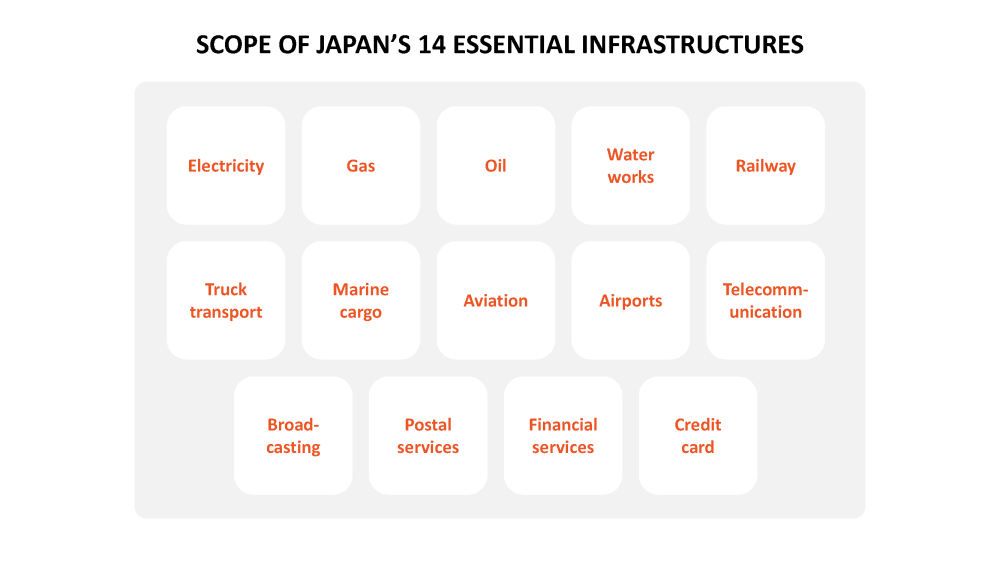

- Second pillar (critical infrastructure): The Japanese Government identifies applicable infrastructure-related business entities in 14 areas (see figure below), assesses the required plan on installation and outsourcing of maintenance and management of key facilities (in a 30-day screening), and makes recommendations and/or orders to the business entities on necessary measures to prevent disruptions. Japan’s National Center of Incident Readiness and Strategy for Cybersecurity (NISC) leads this pillar.

- Third pillar (DCTs): The Japanese Government provides financial support, promotes public-private cooperation and launches an economic security-focused think tank to research DCTs. The Council for Science, Technology and Innovation (CSTI) together with NSC may drive this pillar.

- Fourth pillar (non-disclosure patent): Japan’s Cabinet Office will review a patent application from a specified technology point of view. Then, after passing the security review, the Japanese Government gives security designation, which allows the patent to prohibit application withdrawal, forbid disclosure and require appropriate information management.

Source: Koki Shigenoi /Nikkei, 21 October 2022

Challenges and Practices

In practice, Japan’s pioneering agenda on economic security faces a number of challenges. The greatest challenge may be the so-called ‘stove-piping’ of the Japanese bureaucracy – i.e., instead of making decisions, ministries spend inordinate amounts of time fighting over turf. While the Japanese Government created the Economic Security Promotion Office at National Security Secretariat and subsequently established the ministerial post, individual cases will still be assigned to each ministry. For instance, for issues regarding supply chains (the first pillar), the ministries in charge of reviewing and licensing company applications differ according to sector. Under the current coverage, METI handles a significant portion of these cases, but this concentration of authority may be undesirable for other ministries, especially when the project is crucial to the Japanese administration. Due to the overlap of economic security topics across the ministries’ coverage, many of these supply chain and critical infrastructure cases should be addressed in a cross-functional manner rather than as stand-alone responsibilities.

The scope of economic security is broad, and addressing these challenges requires a speedy response. Therefore, it is necessary to build a system with a clear leadership and coordinating role. In Japan, this coordination role should be fulfilled by either the Cabinet Secretariat or the National Security Secratariat’s economic section under the economic security minister’s leadership. Ministries and agencies should work together horizontally to tackle the challenge rather than following the current stove-piping model.

Source: Koki Shigenoi /Nikkei, 21 October 2022

Implementing a system of clear coordination on economic security allows for centralized management and simplified decision-making. It will also make it easier to cooperate with other countries, which is essential for this new approach to succeed. International cooperation with like-minded partners is an important alternative to relying on excessive reshoring. Since longer supply chains are more vulnerable, many in Tokyo argue that supply chains should be shortened by moving production back to Japan – but this solution would be severely inefficient. Rather, cooperation with like-minded partners can help to establish trusted, more secure supply chains.

Although it does not say so explicitly in public documents, the ultimate goal of Japan’s economic security policy is to reduce its dependence on China, and thus protect its industries from Beijing’s coercive economic statecraft. But efforts to reduce dependence on a single country or to restructure supply chains are easier said than done. In the last decade, many Japanese companies have moved their manufacturing out of China. However, the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that transitioning final product assembly away from China only cuts dependence if accompanied by a diversification of sourcing components.

There is also some movement concerning security implementation in Japan’s private sector. Mitsubishi Electric, for example, pioneered the establishment of a company-wide risk management structure by setting up the Corporate Economic Security Division, which it incorporated into its management board. In addition, global consulting firms such as PwC Japan and EY Japan have established economic security consulting divisions to advise private companies on their economic security-related practices. It is likely that Japan’s private economic security implementation will proceed in this way: with companies developing organizational structures to deal with economic security based on the advice of consulting and law firms and reviewing their own business portfolios — particularly supply chain management — and investment strategies.

Lessons for Germany’s Economic Zeitenwende

Currently, Japan is in the process of revising its National Security Strategy after nine years. Economic security is expected to play a prominent role not just in the updated strategy, but also in Japan’s G7 Presidency in 2023. Here, Germany should take Japan’s lead and include its own economic security policy in its upcoming National Security Strategy.

The term ‘economic security’ has no clear definition: instead, the concept should be understood as an umbrella notion. Thus, it is necessary for each country to define key issues and develop legal systems and organizational structures in accordance with its own industrial needs and challenges. For Germany, matters related to export and investment control, data regulation, telecommunication standards, and patents should be prioritized at the EU level. In addition, shaping international partnerships in key areas will be significant for Berlin. Here, the Chip 4 Alliance on semiconductor manufacturing — which includes Japan, the United States, Taiwan, and South Korea — can offer important lessons.

While the German Government is responsible for enacting laws, formulating a strategy and giving its security policy a direction, implementation will ultimately fall to the private sector. In the end, national and corporate interests often differ, and there are clear trade-offs between a focus on economic growth and a focus on economic security. What costs are acceptable in the pursuit of greater economic security is up for debate. The ideal balance between securing economic security and achieving economic prosperity remains elusive – for now.

Still, Berlin needs to take a greater economic role that is not guided by short-term market growth alone. For its economic Zeitenwende, Germany can look to Japan, where efforts toward economic security are still in an experimental phase. That makes now the right moment for Tokyo to engage in peer-learning with Berlin. The first-ever Japanese-German government consultations scheduled for early 2023 involving both states’ full cabinets provides a good opportunity for doing so.

Koki Shigenoi

Research Associate, Asia-Pacific Department, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung

Keep on reading

Bringing the Indo-Pacific into Germany’s Security Strategy

Germany’s first-ever national security strategy represents an opportunity to re-examine how Germany sees the world – not just the developments in Europe, but also those in the Indo-Pacific.

Finding a New Compass for Germany’s Foreign Economic Policy

Germany has one of the world’s most internationalized economies. This comes with benefits, but also with risks. Berlin’s national security strategy is an opportunity to recalibrate its foreign economic policy to better maneuver today’s challenges.

Security through Preparedness: Lessons from Australia and the Indo-Pacific

For any country with strong stakes in a rules-based order, China’s recent aggressions in the Indo-Pacific should set off alarm bells. It’s time for new thinking about national preparedness – as Australia has learned in recent years.