How to Trump-Proof Germany’s National Security Strategy

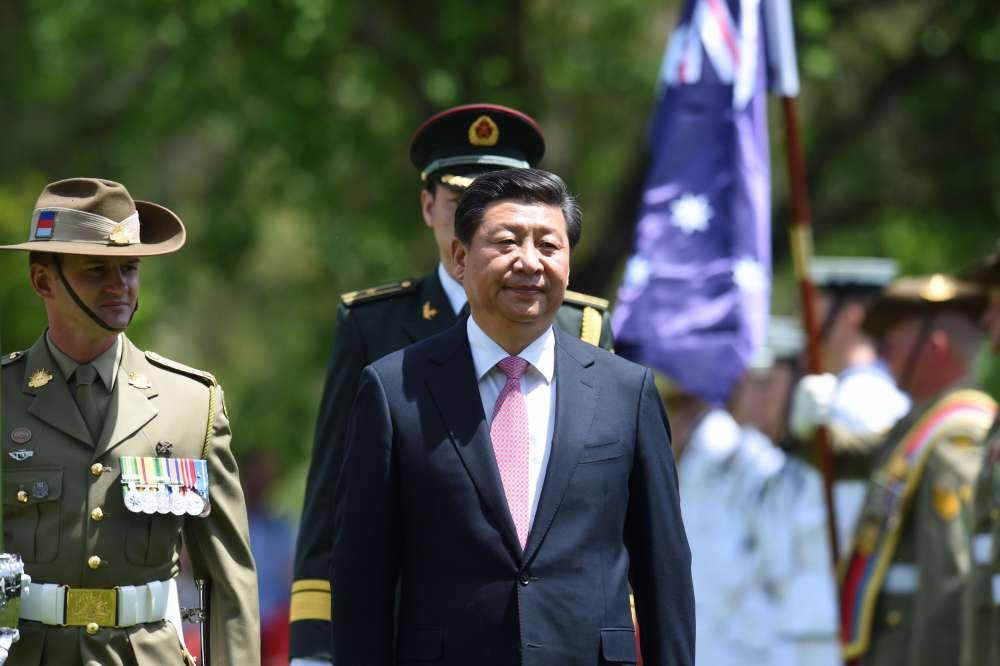

Photo: Leigh Vogel/UPI/Shutterstock

The Biden administration may make for a soothing partner, but it will not be in office forever. Instead of fretting over Trumpism, Berlin should accept its power to improve ties with Washington regardless of who moves into the White House next.

The inauguration of Joe Biden as president of the United States came as a relief to Germany. Now that Biden’s political fortunes are faltering, and his predecessor is eyeing a comeback in 2024, Berlin’s foreign policy hands worry that past is prologue: Donald Trump, not Biden, may end up with the last word on German-American relations.

These fears are fueled by regular portrayals in the German press of the Republican Party as gripped by a Trumpian fever. Even without Trump, so the narrative goes, hostility toward Germany has become a mainstay of GOP thought. Many Germans believe that when the Republicans return to the White House, ties with the United States will inevitably sour again.

Trump’s tasteless criticisms of Germany make him an easy target for his opponents. And by going beyond fence-mending to blaming most transatlantic ills on his predecessor, Biden has reinforced the German tendency to focus on Trump. But fretting about Trump robs Germany of political agency — and obfuscates its own responsibility. Instead of succumbing to handwringing, Berlin has within itself the power to improve its standing in Washington on both sides of the aisle. This requires a sea change in German attitudes, which the war in Ukraine can help bring about. In the security domain, three areas of self-reflection present themselves most immediately: strategic culture, military capability and responsible leadership.

» Instead of succumbing to handwringing, Berlin has the power to improve its standing in Washington on both sides of the aisle. This requires a sea change in German attitudes. «

A New Strategic Culture

Since the end of the Balkan wars, Germany has eschewed tough questions related to security, dismissing American concerns as mere shibboleths, and gone off into an imaginary twilight where no external evil prowls. Until recently, it was as if Germany did not fear any strategic threat. Since the world today is more dangerous than at any time since the advent of modern warfare, this was a curiosity that has led many Americans to conclude that Germany is a free rider.

Vladimir Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine is a baptism by fire. Looking beyond the current conflict, however, Germans might recognize that a serious security force exists because the state needs it to exist, not specifically to target an enemy. In other words, Germany must develop a strategic culture that is at ease with, and appreciates the importance of, hard power. Berlin has compelling reasons to fear militarization, but democracy and security must coexist for a society to thrive.

» Berlin has compelling reasons to fear militarization, but democracy and security must coexist for a society to thrive. «

This requires raising the social capital necessary to support a professional force, both politically and technically. It will take time for Germany to develop its non-commissioned officers, who are the middle managers of any force and the backbone of top-flight militaries. To imbue those soldiers with national pride and professional spine, Germany will need to double-down on its education and training institutions, including its staff colleges and battle schools.

Most of all, Berlin must wrestle with the same vexatious questions which challenge all societies: How large a military? How can the Bundeswehr attract and retain the technologically savvy and educated soldiers needed to employ modern weapons? And how will such a rebuilt army – and its associated structures – interact with the private sector, academia and civil society?

Key Points

- Germany’s military response to Russia and its economic answer to China are the twin axes on which the US-German alliance will rotate for the foreseeable future.

- Today’s Republican Party is mainly focused on securing America’s national interest. Still, Berlin should take responsibility for improving its standing in Washington on both sides of the aisle.

- Germany has allowed its military to decay alarmingly. Rebuilding the Bundeswehr will require major spending efforts stretching over years, if not decades.

- In the case of war over Taiwan, the US will expect Germany to lead Europe in an economic embargo against China.

An Upgrade of Military Capability

Over the past three decades, Germany has allowed its military to decay alarmingly. As one former German general officer put it to me recently, the Bundeswehr has been demoted to a disaster relief force. Today, Germany does not even have the military wherewithal to mount a credible defense for itself, much less to be a significant asset to its allies.

As far back as the late 1990s, Germany cannibalized various military units to fully kit out an expeditionary force for the international mission in Kosovo. The situation has not improved in the intervening years. Germany lacks troops, equipment, logistics, and training in critical areas of modern military power. It also has not kept up with the technological transformations of recent decades: missing are precision-guided munitions, new ballistic technologies, modern radars, drones, robots, ablative armor, blast-resistant vehicles, and all manner of electronics, to name only a few essentials of 21st-century warfare.

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s announcement of major new defense outlays temporarily silenced Germany’s critics in the United States. But it will be essential for Germany to stay the course – with major spending efforts stretching over years, if not decades, even as the immediate shock of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine fades. A serious military cannot be built over just a few budget cycles.

» A serious military cannot be built over a few budget cycles. «

A New Form of Responsible Leadership

Germany must also determine its strategic purpose. What role does it intend to play in Europe and beyond? Loosely, the tradition has been that the French lead, the Americans fight, and the Germans produce. Because Germany was the epicenter of the Cold War, few analysts questioned such a division of labor. Now that the focus of conflict has moved east, from Ukraine to Syria to the Pacific, Germany is no longer the center of the US-led strategic world. Berlin must develop a role for itself – and a new relationship with its allies – post-Cold War.

Germany has already asked – and answered – its own existential security question several times in the past: What is necessary for us to be secure? For Adenauer, it was Westpolitik. For Brandt, it was Ostpolitik. And for Kohl: Europolitik. Sometimes these approaches worked and sometimes they did not, but at least they offered clearly visioned directions. Absent such a vision, it is unclear what kind of political, economic and military role Germany intends to assume in Europe going forward.

Looking Beyond Trumpism

Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has demonstrated to many Germans the foolishness of their country’s post-Cold War slumber — and the value of the United States as an ally. But while the Biden administration may make for a comfortable, soothing partner, it will not be in office forever. Meanwhile, the Republican Party, should it assume power next, is not the same organization that staffed the administration of George W. Bush. It no longer prioritizes democracy promotion, nor is it animated by professions of faith in the liberal international order. Instead, it is focused more narrowly on securing America’s national interest.

» Sino-American competition is now the dominant dynamic in today’s international system, and how open societies defend themselves against bad actors in an era of globalization is its central conundrum. «

In Europe, doing so begins for the US with deterring Russia – but it does not end there. Sino-American competition is now the dominant dynamic in today’s international system, and how open societies defend themselves against bad actors in an era of globalization is its central conundrum. Because there are three, and only three, major powers centers in the world today – East Asia, North America, and Europe – it is only natural for the US to look to the latter, its civilizational cousin and democratic partner, for support against China. The next Republican administration will strive to align policies with Germany on everything from export controls to investment screening. Unlike the Biden team, however, the GOP’s historical resistance to lowest-common-denominator multilateralism means it will not shirk from pressing the envelope, like urging a decoupling in national security sectors and consequences for Beijing’s serial violations of basic trading rules. In the case of war over Taiwan, the US will expect Germany to lead Europe in an economic embargo against China.

Germany’s military response to Russia and its economic answer to China are the twin axes on which the US-German alliance will rotate for the foreseeable future. By setting out an agenda that accepts responsibility in both realms, Germany can reestablish its value to the next Republican administration, be it Trumpian or not.

Peter Rough

Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute

Keep on reading

It’s the Politics, Stupid: Lessons for Germany from US Security Strategies

A successful national security strategy needs a solid political foundation. In democracies, that foundation – for better or worse – rests on the electoral process and the political leaders it produces.

Better Safe than Sorry: Lessons from Finland

In the process of its security policy rethink, Berlin has the chance to become a capable security ally for the Nordic region. Germany may have a lot of catching up to do, but its northern neighborhood can offer the right peer group with which to join forces.

Security through Preparedness: Lessons from Australia and the Indo-Pacific

For any country with strong stakes in a rules-based order, China’s recent aggressions in the Indo-Pacific should set off alarm bells. It’s time for new thinking about national preparedness – as Australia has learned in recent years.